People have always been able to take photos of themselves—however, it used to require a tripod, a timer, and a quick run to get in place. But ever since Apple introduced a front-facing camera on the iPhone back in 2010, the “selfie” has become an international phenomenon, with Samsung estimating that the average person will take over 25,000 selfies in their lifetime. That average is heavily skewed by age, with Millennials leading the pack with an estimated one hour each week spent taking and editing selfies, whereas Baby Boomers may snap only a few on special occasions. It also varies by country, with selfies being particularly popular with young people in China and India.

While the single term “selfie” sounds simple, it really covers quite a range of photographic situations captured by the front-facing camera on a phone. And, too, there is a wide variety of skin tones and facial features that selfie cameras must capture, render, and perhaps enhance. So when we designed our protocol for testing and scoring front-facing phone cameras — DxOMark Selfie—we needed to take into account all of those factors.

Early selfies

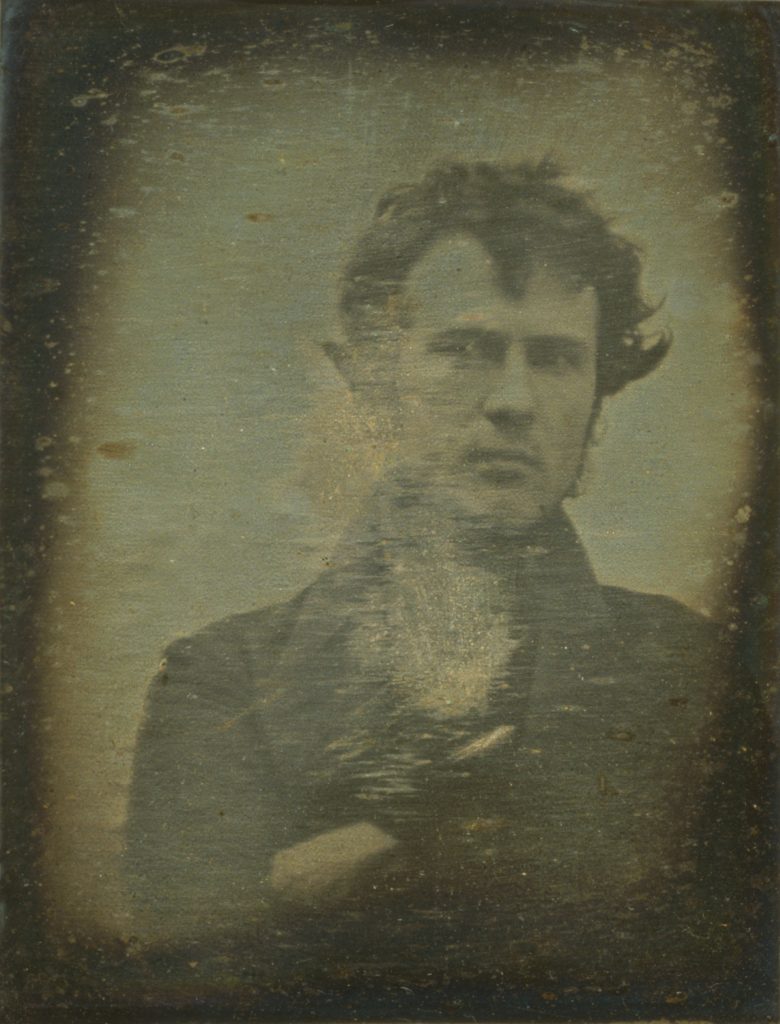

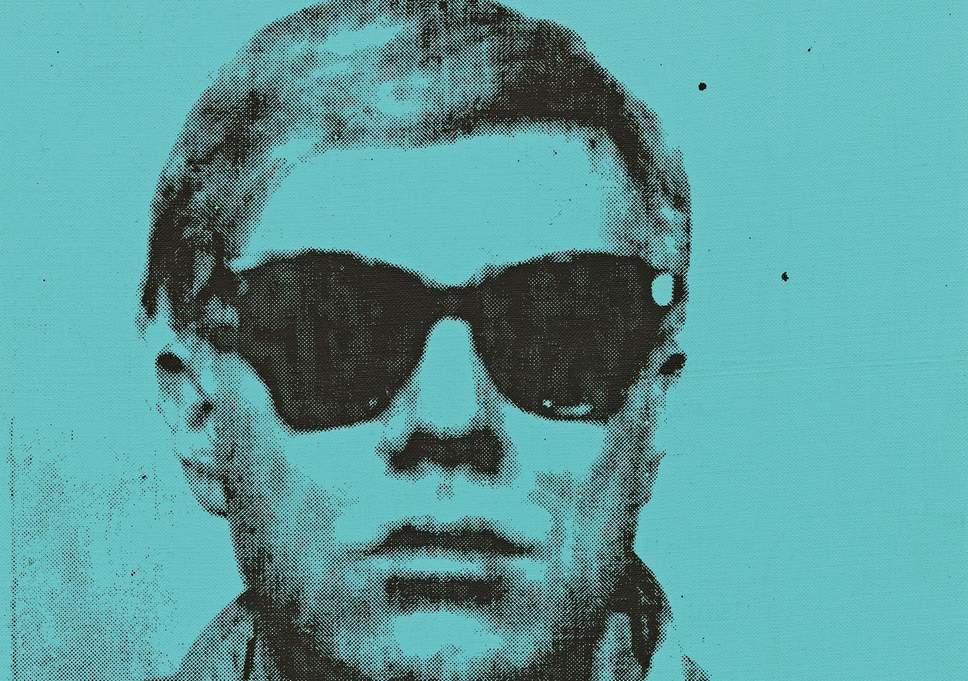

Although self-portraiture has a long history, the first known photographic selfie was a time-consuming effort by chemist Robert Cornelius in 1839. Around the same time, Hippolyte Bayard was testing his photographic process with self-portraits before showing it to the French academy of science. But it wasn’t until Andy Warhol made selfies into an art form in the mid-1950s and beyond that they started to receive more attention. Even so, until the advent of social media and profile photos, there wasn’t really much use for them. MySpace introduced profile photos in 2006, but by 2009, MySpace had been eclipsed by Facebook. Until front-facing cameras in smartphones became more common, however, selfies were hard to capture, and were often taken by friends. Once selfies became mainstream, it wasn’t long before filters from Instagram and other apps helped people tweak their selfies — giving them even more motivation to capture and share them more frequently.

Selfies in the age of social media

2012 brought video selfies to Snapchat. Later, Instagram introduced its similar “Stories” feature that also showcased selfie videos. 2014 saw the introduction of the term “selfie stick” to describe various devices designed to hold the phone at more than arm’s length, greatly broadening the options for dedicated selfie shooters. That same year, Google estimated Android phones alone were used to capture about 93 million selfies every day. At about the same time, phone makers started to realize the increasing importance of the front camera, and began improving its resolution and image quality. By 2015, people had uploaded 25 billion selfies via Google’s Photos app alone.

Research shows that over half of all selfies shared online are part of posts that concern physical appearance, so image quality and image enhancement have become key features of capturing portraits with front-facing cameras. Women posted two-thirds of such selfies, especially women between 18 and 35 years old, although those under 18 were also active sharers. Other categories of shared selfies, including posts with friends, pets, travel, and ethnicity, trailed fairly far behind. Overall, 87% of U.S. smartphone users between the ages of 18 and 35 have shared at least one selfie. Worldwide, people have installed selfie-editing apps from Chinese vendor Meitu on well over a billion smartphones, most of them in China. China has even brought selfies full circle, with the introduction of Selfie Studios, where customers can choose from professionally-designed sets, lights, and costumes to provide the setting they want for their selfie.

Types of selfies and camera challenges

Selfies are a particularly challenging type of photograph for a camera to capture, as skin tones and complexion vary widely around the world, as do aesthetic tastes. Selfie users also vary in what they want from the final image. As a simple example, Meitu found that users in Norway liked leaving their freckles in the photo, while those in its native China wanted to remove any type of marks or blemishes.

If you’re not a selfie aficionado, you may think that all selfies are pretty similar. In reality, there are several quite distinct types of selfie, each of which poses different challenges in terms of exposure, focus, auto white balance, and other camera features. The most important categories are self-portraits, group shots, shots that highlight a location, and videos.

The “traditional” selfie is a simple self-portrait. They are often used to show off a hairstyle, an outfit, makeup, or for uploading as a profile photo to a social media service. In some countries, such as China, it is also common for job-seekers to send a headshot with a job application, and many of those are captured as selfies. Unfortunately, smartphone front cameras held at arm’s length aren’t ideal for shooting portraits: faces become distorted and noses look larger, for example. So it is crucial to be able to assess how pleasing a smartphone’s rendering of faces is — including geometry, skin tone, and complexion.

Another popular type of selfie is a group selfie, taken either at arm’s length or with a selfie stick. This type of shot adds additional difficulties for the camera. First, different subjects will be in different parts of the image, and therefore will be subject to different types and amounts of distortion. They’ll also be at different distances, which means that a larger depth of focus is required. Additionally, the group may have a variety of skin tones, so it may be difficult to choose the best combination of exposure and white balance for the image. It is particularly difficult for the camera to do a good job if the subjects include individuals with both very light and very dark skin colors.

In travel selfies, often shot with the help of a selfie stick, the image background is an important element of the scene. Here the problem of skin tone exposure is amplified, as the person may be in different light than the background, and it may be difficult to correctly expose for all the subjects in a shot as well as for the background. In addition, the camera needs to also do a good job of rendering the background, as it is typically a memorable destination or experience that the photographer wants to capture and share. Instead of blurring the background, the goal here is to have the entire image sharp.

It’s not all about still images, though. The growth in video selfies is massive as well. Platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat all now offer features for posting and live-streaming of selfie-video, effectively allowing users (who previously were mainly consumers of content) to turn into creators and live entertainers. Vloggers on Youtube increasingly complement material from DSLRs, mirrorless cameras, or action cams with footage from their smartphone front cameras.

In addition to these more conventional social media apps, several new app concepts have emerged that allow users to become creators and performers with the help of selfie video. Apps such as Dubsmash or Musical.ly let you record yourself lip syncing music and are particularly popular with a younger audience. Kombie allows you to insert yourself into any any piece of video or film footage with the press of a button—for example, a music video or a scene from your favorite movie. The results is an interactive video selfie that can be instantly shared.

Selfie video has essentially become a new way of communication, particularly for the younger generations, and of course, any type of video calling done with a smartphone is another example of a selfie video. Initially, phone users were happy enough just to be able to share videos, and put up with distorted faces and other image imperfections, but increased use and popularity has raised the bar, and customers now want some of the same image quality in their selfie videos that they can already get in their selfie stills. Some modern smartphones are now capable of doing real-time video enhancement that is specific to portraits.

DxOMark Selfie

When we designed our new DxOMark Selfie test protocol for evaluating and scoring smartphone front cameras, we had to take into account all the regional differences in taste and cover all the different selfie use cases described above. This meant custom-designing new test environments and new test scenes — all of which need to be flexible enough to accommodate the global audience of selfie-takers.

We use human subjects with a variety of skin tones and complexions in our testing. In addition to those human subjects, we also worked with a Hollywood special effects studio to create several custom mannequins that have been carefully designed to accurately mimic human skin tones under a variety of lighting conditions.

For in-depth details about our smartphone front camera testing, please read our articles, ”How we test smartphone front camera still image quality” and “How we test smartphone front camera video quality,” along with our Introduction to our new DxOMark Selfie test protocol.

English

English 中文

中文

DXOMARK invites our readership (you) to post comments on the articles on this website. Read more about our Comment Policy.